Art is a world generally acknowledged to be in a state of constant flux. In few other fields of human endeavour is rapid, dramatic change expected and accepted as readily or sought after so constantly. From primitive man’s first murals of horses, bulls and bears from 31,000 BCE, to the painted pottery of Ancient Greece, to the sublime oil on canvas technique of Leonardo da Vinci and the visual revolution of Cubism lead by Pablo Picasso, the way our world has been continually represented in new ways is truly remarkable.

Michelangelo, Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Rembrandt, Paul Cezanne…Despite their differences in form, the aforementioned artists have two things in common: 1) Their work is exceptionally well-regarded and valuable; and 2) They were all human. The second point may seem obvious to the point of being bizarre, as many people would probably not consider anything other than a human being actively pursuing the arts – although there are certainly examples of animals taking up the brush (with varying degrees of success). However, a painting was recently sold at Christie’s in New York for an impressive $432,000; its creator wasn’t human, animal, or even alive: it was created by AI.

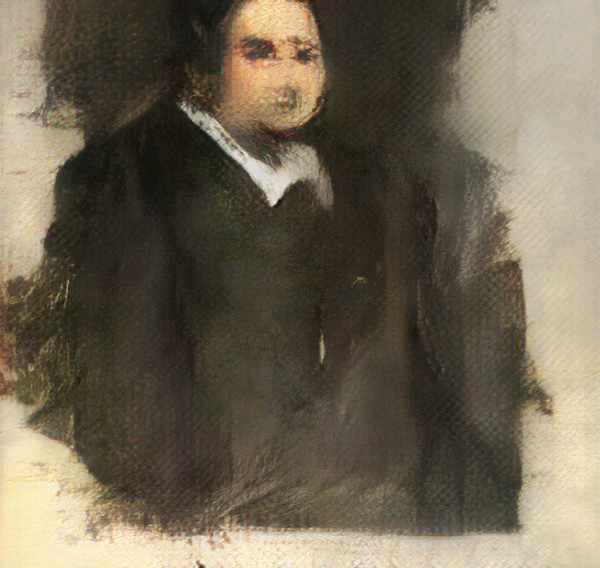

As you can see, the painting – entitled ‘Edmund de Belamy’ – was not painted by brush, but is rather a series of coloured ink-dots on a 27.5”x27.5” canvas set within a gilded frame. Up close, the painting doesn’t look like much else, but by stepping further away, it comes together to form the mysterious image of its subject. For the mathematically-minded, the algorithm code that helped create the image is ‘signed’ at the bottom of the canvas, as a kind of nom d’artiste for the AI.

Okay, okay; it’s not exactly the Mona Lisa, but how did this come about? It all began with the French collective Obvious, a group of artists/friends/researchers who discovered something called Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs); these are learning algorithms for machines that are capable of generating unique images. The AI was given 15,000 examples of pre-20th Century portraiture as a ‘stylistic baseline’ and was then let loose to create its own original image. As you can see, the AI struggles with the finer details of the human face, and this is a recurrent flaw with its process (as evidenced in other examples of its work, which can also be found at obvious-art.com), but nevertheless, the AI’s concept/intent is arguably quite obvious.

Yet always the question lingers, like the poisonous whisper of Rudyard Kipling’s devil in his poem Conundrum of the Workshops, “It’s pretty, but is it art?” What is and isn’t ‘art’ is a difficult question, and one left largely to beholder. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp exhibited a men’s lavatory urinal, un-modified save for a pseudonym that Duchamp had signed it with. In the late 40’s, Jackson Pollock displayed paintings that had no conventional form at all, having been composed by randomly dripping paint onto the canvas. These artists have subsequently grown in renown over the years, both for their originality of vision and for challenging the popular conventions for what constitutes ‘art’. Now, ironically, these once-derided works are part of mainstream culture.

So, can ‘Edmund de Belamy’ genuinely be considered a piece of art? The painting, originally appraised at only a few thousand dollars, performed exceptionally well at auction, indicating clearly that, at the very least, there is a paying market for such works. Unusual form can hardly be a criticism either, as the movements of Impressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism proved that life-like accuracy should never interfere with an interesting idea. Perhaps the more appropriate questions would be: is the AI actually an artist? Is a machine creating independently from a foundation of previous works significantly different to the creations of any art student? Is the AI’s fulfilment of a task at the behest of its programmer so far removed from the archetypal ‘struggling artist’ painting for his/her patron?

Hungarian painter Elmyr de Hory, one of the most infamous art forgers in history, had a philosophy: a fake piece of art can be as good or even better than the real thing, so long as it still ‘moves’ the viewer genuinely. Given that this picture has already caused a stir in the art world, and that the advancement of AI is less a question of ‘if’ than ‘when’, we can surely look forward to an ongoing debate about whether machines ever could be artists in their own right.